AI in OSINT Investigations: Balancing Innovation with Evidential Integrity

The Coalition of Cyber Investigators join forces with Tesari AI to discuss why the use of AI in OSINT investigations must balance innovation and technology with evidential integrity.

Paul Wright, Neal Ysart & Elisar Nurmagambet

2/8/202612 min read

AI in OSINT Investigations:

Balancing Innovation with Evidential Integrity

1. Introduction: The AI Revolution in OSINT

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is now central to Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT). In law enforcement, journalism, corporate investigations, and intelligence analysis, AI tools are being tested, praised, distrusted, informally used, and sometimes resisted. This mix generates both excitement and unease, reflecting the complexities of adoption[1].

The fact is that with AI doing the heavy lifting, massive volumes of data that used to take weeks to collect can be gathered in hours. Patterns and trends that humans would typically miss are quickly identified, making it manageable for analysts to deal with massive data sets rather than being overwhelming[2]. However, it may generate plausible but unsupported responses. Integrating AI is not the question - this is happening - the real challenge is whether its use upholds evidential standards and investigative credibility.

A critical distinction often overlooked in public discourse is between general-purpose AI systems, such as ChatGPT, and specialised investigative platforms like TESARI[3]. General-purpose AI is built for broad conversational and summarisation tasks. AI tools built specifically for investigative workflows, where accuracy and evidential reliability are crucial, as mistakes can have serious repercussions for the validity and admissibility of the findings and for the investigator's reputation. Treating these two types as equivalent misses the point and glosses over the unique challenges and safeguards needed for investigative work[4].

The central question this article addresses is whether current AI tools, particularly those used in OSINT environments, are effectively addressing established investigative challenges without introducing new issues that compromise forensic integrity. More specifically, it examines whether the pursuit of efficiency is being prioritised at the expense of investigative rigour.

2. Understanding the OSINT AI Ecosystem

The current OSINT AI landscape is fragmented and lacks cohesion. Not only that, when examining the experiences of investigative journalists, boutique firms, due diligence teams, and corporate compliance units, it appears that only a small group of early adopters are deriving substantial value from AI. These users tend to be careful, methodical, and skeptical. In contrast, many others are overwhelmed and uncertain about how to integrate AI[5] or explain its use to courts, formal proceedings, regulators, or internal management.

AI tools are infrequently integrated into formal investigative workflows. Instead, they often function as unofficial assistants, providing analysts with increased speed or clarity. While this informal use is understandable, it introduces significant risks.

Specialised AI Platforms: A Different Philosophy

[1] Wright, P. and Ysart, N. (2025) ‘The Evolution of OSINT: How AI and Human Expertise Work Together’. Available at: https://coalitioncyber.com/the-evolution-of-osint-how-ai-and-human-expertise-work-together (Accessed November 2025)

[2] Mitchell,S.(2026) ‘OSINT investigators battle data glut & scarcity with AI’, Available at: https://securitybrief.co.uk/story/osint-investigators-battle-data-glut-scarcity-with-ai (Accessed on January 2026)

[3] ‘Tesari’ https://tesari.ai/

[4] Wright, P. and Ysart, N. (2025) ‘A Raw Take on OSINT's Broken State - Time for Real Change’. Available at: https://coalitioncyber.com/osints-broken-state (Accessed November 2025)

[5] Wright, P. and Ysart, N. (2025), ‘A Watershed for Intelligence Professionals’. Available at: https://www.osint.uk/content/a-watershed-for-intelligence-professionals (Accessed October 2025)

[6] National Police Chiefs’ Council (2025) ‘Artificial Intelligence (AI) Playbook for Policing’. Available at: https://library.college.police.uk/docs/NPCC/Artificial-intelligence-playbook-policing-2025.pdf (Accessed October 2025)

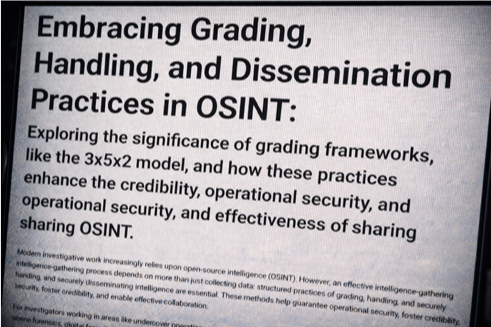

[7] Wright, P. and Ysart, N. (2024), ‘Embracing Grading, Handling, and Dissemination Practices in OSINT’. Available at: https://coalitioncyber.com/embracing-grading-handling-and-dissemination-practices-in-osint. (Accessed November 2025)

[8] Crown Prosecution Guidance (2022) ‘Disclosure Manual: Chapter 30 - Digital Material’. Available at: https://www.cps.gov.uk/prosecution-guidance/disclosure-manual-chapter-30-digital-material (Accessed December 2025)

[9] Palo Alto Networks Cyberpedia (n.d) ‘Black Box AI: Problems, Security Implications, & Solutions’. Available at: https://www.paloaltonetworks.com/cyberpedia/black-box-ai#:~:text= (Accessed November 2025)

[10] DQI Bureau (2025) ‘AI on trial: What regulators and judges really expect’. Available at: https://www.dqindia.com/features/ai-on-trial-what-regulators-and-judges-really-expect-10895556 (Accessed November 2025)

[11] Fisher, KC.J. (2025) “Disclosure in the Digital Age: Independent Review of Disclosure and Fraud Offenses”. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-review-of-disclosure-and-fraud-offences/disclosure-in-the-digital-age-independent-review-of-disclosure-and-fraud-offences-accessible (Accessed December 2025)

[12] Courts and Tribunals Judiciary (Judicial Office of England & Wales) (2025) ‘Artificial Intelligence (AI) Guidance for Judicial Office Holders.’ Available at: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Artificial-Intelligence-AI-Guidance-for-Judicial-Office-Holders-2.pdf (Accessed January 2026)

[13] Privacy Culture (2025) ‘How AI is changing evidence disclosure in the UK. Available at: https://privacyculture.com/news-article/104/how-ai-is-changing-evidence-disclosure-in-the-uk (Accessed December 2025)

[14] United Nations System Chief Executives Board for Coordination. (2023) ‘International Data Governance – Pathways to Progress’. Available at: https://unsceb.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/Advance%20Unedited%20-%20International%20Data%20Governance%20%E2%80%93%20Pathways%20to%20Progress_1.pdf (Accessed January 2026)

[15] Office of the Director of National Intelligence. (2024) ‘The IC OSINT Strategy 2024–2026. U.S. Intelligence Community.’ Available at: https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/IC_OSINT_Strategy.pdf (Accessed January 2026)

[16] Bochert, F. (2021) ‘OSINT – The Untapped Treasure Trove of United Nations Organizations.’ Available at: https://hir.harvard.edu/osint-the-untapped-treasure-trove-of-united-nations-organizations/ (Accessed January 2026)

[17] World Customs Organization (WCO), Unlocking the Value of Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) for Customs Enforcement: Study Report (July 2024). Available at https://www.wcoomd.org/-/media/wco/public/global/pdf/topics/enforcement-and-compliance/activities-and-programmes/security-programme/osint-report_final.pdf (Accessed February 2026)

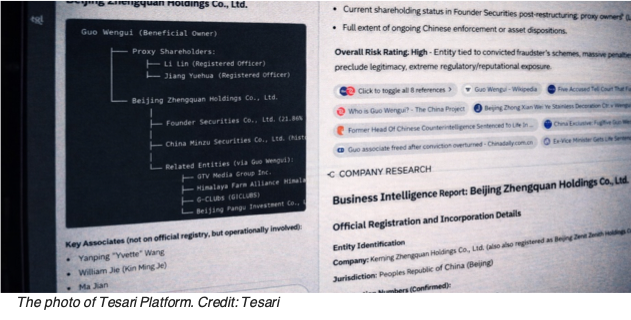

Purpose-built investigative platforms, such as TESARI, adopt a fundamentally different approach from consumer AI systems. Instead of positioning AI as an autonomous answer engine, these platforms utilise AI as a collaborative tool that assists, suggests, and correlates information, but does not make final decisions. This distinction is critical for maintaining investigative standards[6] especially when investigators, analysts, and forensic specialists may complain loudly when outputs cannot be defended. They prioritise global source coverage, including jurisdictions most tools conveniently ignore, for example, Russia, China, and fragmented or hostile information environments.

Ethical frameworks are not decorative add-ons but operational necessities, particularly where investigations touch organised crime, terrorism, or trafficking networks.

Most importantly, these systems are designed to complement rather than replace existing investigative tradecraft. While this design choice may restrict specific AI capabilities, such limitations are often essential to preserve credibility. Furthermore, general-purpose AI excels at breadth, processes enormous volumes of language, synthesises ideas fluently, and responds instantly. But it does not understand evidential thresholds. It cannot inherently distinguish a rumour from a corroborated fact unless explicitly told how, and even then, inconsistently.

This situation introduces a significant risk: AI-generated outputs may resemble intelligence assessments but lack the evidential structure required by investigators. Generic summaries can be mistaken for analytical conclusions, and linguistic fluency may be misinterpreted as authority. In high-stakes domains, such risks cannot be justified on the grounds of convenience.

3. Critical Vulnerabilities: Where AI Falls Short

Despite its potential, AI possesses structural weaknesses that conflict with the requirements of investigative practice.

At its core, most AI systems are probabilistic. They predict likely outputs based on patterns, not truths anchored in verification. That distinction may sound academic, but it cuts directly to the heart of intelligence standards. Traditional models - such as the UK 3x5x2 system[7] - exist precisely to force analysts to separate source reliability, information credibility, and confidence. AI does not do this naturally. It blends everything into something neat and This pattern increases the chance of producing “plausible intelligence” which appears credible but is not actually backed by evidence. In active investigations, such false confidence can push investigators down the wrong path.

AI hallucinations can make the problem even worse. Fabricated links that look genuine, invented causality, or unsubstantiated attribution can all look convincing and be difficult to detect. In threat assessments or sensitive criminal cases, such errors can contaminate decision-making processes, resulting in subtle but significant distortions rather than overt failures.

Language adds another layer of fragility. Sarcasm, slang, regional idioms, and coded speech are frequently misread by AI. Online identities blur. Handles overlap. Context collapses when threads are deleted or accounts migrate. A human analyst senses these gaps instinctively; AI does too. A worrying trend is AI’s ability to frame shaky conclusions as solid facts. Unless explicitly programmed to indicate uncertainty, AI systems are unlikely to flag it. This transparency gap can lead investigators trust an output that should be treated with skepticism.

4. Forensic Integrity and Evidentiary Standards

These challenges become especially pronounced when investigations cross into formal legal or regulatory proceedings. This section examines the implications of such transitions.

Chain of custody, for instance, is not a theoretical concern. Many AI tools cannot demonstrate how data was handled, transformed, or stored at each step. Microsecond-level logging is rare.

Provenance tracking[8] is often incomplete. Sources become commingled, inference tangled with raw data. Once that happens, evidential value degrades rapidly.

The so-called “black box”[9] problem exacerbates this. Courts and regulators do not accept “the model said so”[10] as an explanation. Investigators must explain how they concluded. Without transparent reasoning pathways, AI-assisted findings risk exclusion, or worse, reputational damage when challenged[11].

Specific mitigation strategies are available.

Iterative prompting can be used to partially reconstruct the reasoning process and help maintain a clear separation between the data that was collected and analysed and what the AI inferred. However, this is still a workaround or compensatory control, not a comprehensive solution.

Additionally, the legal admissibility of AI-assisted OSINT isn’t clear – we don’t yet have a globally accepted body of case law. Very few AI-OSINT methodologies have been tested in court, and expert witnesses who can clearly explain AI processes to a judge[12] or jury are also scarce. Until these gaps are addressed, caution in using AI should be regarded as a mark of professionalism rather than conservatism.

5. Mitigation Strategies and Compensating Controls

Responsible integration of AI depends more on disciplined processes than on the perfection of individual tools.

Human-in-the-loop review is non-negotiable. Analysts must verify tone, context, and meaning. They must annotate uncertainty rather than smooth it away. Subject matter experts should interrogate outputs, and source verification should be strengthened rather than replaced. Automated grading systems can provide support but must be aligned[13] with established intelligence frameworks.

Investigators need to identify adversarial content, including misinformation, influence operations, and deception, and flag it, rather than simply accepting it without scrutiny and folding it into your report. It is essential to keep raw data separate from what AI infers without verification. When these elements are conflated, reproducibility is compromised. It’s in these circumstances that a failure to adhere to proper documentation standards makes it almost impossible for other investigators to effectively replicate or challenge findings. Transparency and the ability to audit work are not optional. This includes maintaining timestamped logs, clear provenance, and detailed records of each transformation step. While these measures may lack appeal, they are indispensable.

Alongside technical measures, it is vital to recognise that professional and investigative credibility is highly vulnerable to error. Even minor AI mistakes can persist and undermine trust across the OSINT landscape.

The ethical risks associated with AI use are substantial. Misidentification of individuals constitutes significant harm, not merely a technical error. False accusations carry both legal and moral consequences. Over-reliance on AI increases, rather than diminishes, professional responsibility. The field must respond with urgent commitment to practical safeguards, transparent processes, and ongoing professional scrutiny to ensure that evidence, credibility, and responsibility remain at the centre of AI-integrated investigations.

The balance between risk and reward must be explicitly addressed. Thoughtful use of AI can enhance investigative work, while careless application can have severe professional consequences. Institutions require decision frameworks that acknowledge both possibilities.

6. From Fragmentation to Interoperability: Governance, Partnership, and Shared Tradecraft

The integration of OSINT into investigative practice exposes a widening gap between rapidly evolving operational realities and existing governance, legal, and organisational frameworks. Many current policies were not designed to govern AI-assisted analysis, large-scale open-source collection, or the sensitivity of contemporary digital environments. Addressing this gap requires a coordinated approach that extends beyond tools and workflows to encompass governance, accountability, and shared standards.

While discussions on AI in OSINT often focus on efficiency or admissibility, a more fundamental challenge persists: the absence of coordinated, multilateral governance for the collection, processing, sharing, and reuse of AI-assisted investigative data across borders. OSINT investigations are inherently transnational, spanning jurisdictions, legal regimes, languages, and political contexts. Without shared principles, AI risks amplifying fragmentation - producing incompatible practices that are difficult to explain, defend, or reuse outside their original context.

Institutional adoption of OSINT often encounters resistance driven by concerns about reliability, legal exposure, and accountability. Achieving alignment requires demonstrating value while preserving evidential standards. Early, well-scoped applications can establish credibility, but sustained adoption requires formal policies, defined ownership, and enforceable accountability structures rather than informal or experimental use.

UN data governance frameworks[14] provide a practical pathway toward interoperability without uniformity. They offer shared principles—such as purpose limitation, proportionality, traceability, and human oversight—that allow diverse tools, jurisdictions, and investigative cultures to coexist without undermining evidential integrity. Given the complex and evolving legal landscape around data protection, privacy, and cross-border use of information, organisations must establish clear policies defining permissible use, conduct regular legal reviews, and maintain strict separation between verified data and analytical inference. Ethical standards[15] must be operationalised through training, oversight, and auditable accountability mechanisms.

Interoperability also depends on partnership[16]. The pace of change in the open-source environment - driven by AI, platform fragmentation, and evolving methods of obfuscation—means no single institution or sector can keep pace alone. Sustained engagement with academia, the private sector, civil society, and international partners is essential to maintain both technical capability and investigative tradecraft. Durable cross-border partnerships are particularly critical for investigations involving organised crime, human trafficking, financial crime, and online exploitation, where fragmented approaches weaken both impact and credibility.

Finally, effective OSINT depends on human capacity and operational discipline. Specialised skills in analysis, languages, technical capability, and information security are difficult to recruit and retain. Structured training pathways, continuous professional development, and participation in communities of practice are essential to sustaining capability and institutional memory. OSINT activities should be conducted in controlled technical environments, supported by comprehensive logging, provenance tracking, and audit mechanisms to ensure traceability, reproducibility, and the defensibility of findings, particularly where AI is involved.

The challenge is not to centralise OSINT, but to align it. As AI becomes more deeply embedded in investigative work, multilateral coordination anchored in shared governance principles is no longer optional[17]. In high-stakes environments, such alignment may determine whether intelligence informs action - or fails under scrutiny.

7. The Path Forward: Standards and Best Practice

The lack of global standards for AI-OSINT integration is increasingly unsustainable. Collaboration between the public and private sectors is necessary to define acceptable practices. The development of legally reviewed methodologies, shared quality assurance frameworks, and consensus on high-risk applications is urgently needed.

COLLABORATION BETWEEN THE PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SECTORS IS NECESSARY TO DEFINE ACCEPTABLE PRACTICES.

Training is also essential. Investigators must be aware of both the limitations and strengths of AI. Expert witnesses require specialised preparation. Greater communication and candid discussion among legal, technical, and analytical communities are necessary.

Community-driven innovation presents a promising approach. Platforms informed by practitioner feedback, transparent discussion of failures, and shared lessons are most likely to bridge the gap between experimentation and professional adoption. Ethical guidelines grounded in real-world cases rather than abstract principles are particularly valuable.

8. Conclusion: Analytical Integrity in the AI Era

Investigative AI should be regarded as a powerful but imperfect tool – one that relies on human judgment, rather than as an investigator or analyst in its own right. Specialised platforms demonstrate that responsible integration is achievable, but only when verification, transparency, and accountability are prioritised.

The future of OSINT is not AI versus humans, but it does need humans who understand AI, respect evidential standards, and resist the temptation to trade rigour for convenience. The challenge is ongoing and occasionally frustrating, but if navigated carefully, it offers something rare: innovation that strengthens rather than undermines this dynamic balance. Though imperfect and continually evolving, it is essential that credible AI-enhanced investigative tools continue to develop – we just need to ensure that evidential and investigative principles, as well as humans, are kept in the loop.

Authored by:

The Coalition of Cyber Investigators, Paul Wright (United Kingdom) & Neal Ysart (Philippines), with contributions from guest author Elisar Nurmagambet (CEO and Co-Founder of Tesari AI, a new generation Investigative Platform powered by AI Copilot).

©2026 The Coalition of Cyber Investigators. All rights reserved.

The Coalition of Cyber Investigators is a collaboration between

Paul Wright (United Kingdom) - Experienced Cybercrime, Intelligence (OSINT & HUMINT) and Digital Forensics Investigator;

Neal Ysart (Philippines) - Elite Investigator & Strategic Risk Advisor, Ex-Big 4 Forensic Leader; and

Lajos Antal (Hungary) - Highly experienced expert in cyberforensics, investigations, and cybercrime.

The Coalition unites leading experts to deliver cutting-edge research, OSINT, Investigations, & Cybercrime Advisory Services worldwide.

Our co-founders, Paul Wright and Neal Ysart, offer over 80 years of combined professional experience. Their careers span law enforcement, cyber investigations, open source intelligence, risk management, and strategic risk advisory roles across multiple continents.

They have been instrumental in setting formative legal precedents and stated cases in cybercrime investigations and contributing to the development of globally accepted guidance and standards for handling digital evidence.

Their leadership and expertise form the foundation of the Coalition’s commitment to excellence and ethical practice.

Alongside them, Lajos Antal, a founding member of our Boiler Room Investment Fraud Practice, brings deep expertise in cybercrime investigations, digital forensics, and cyber response, further strengthening our team’s capabilities and reach.

The Coalition of Cyber Investigators, with decades of hands-on experience in cyber investigations and OSINT, is uniquely positioned to support organisations facing complex or high-risk investigations. Our team’s expertise is not just theoretical - it’s built on years of real-world investigations, a deep understanding of the dynamic nature of digital intelligence, and a commitment to the highest evidential standards.